The Black Witch, a debut young-adult fantasy novel by Laurie Forest, was still seven weeks from its May 1 publication date, but positive buzz was already building, with early reviews calling it “an intoxicating tale of rebellion and star-crossed romance,” “a massive page-turner that leaves readers longing for more,” and “an uncompromising condemnation of prejudice and injustice.”

The hype train was derailed in mid-March, however, by Shauna Sinyard, a bookstore employee and blogger who writes primarily about YA and had a different take: “The Black Witch is the most dangerous, offensive book I have ever read,” she wrote in a nearly 9,000-word review that blasted the novel as an end-to-end mess of unadulterated bigotry. “It was ultimately written for white people. It was written for the type of white person who considers themselves to be not-racist and thinks that they deserve recognition and praise for treating POC like they are actually human.”

The Black Witch centers on a girl named Elloren who has been raised in a stratified society where other races (including selkies, fae, wolfmen, etc.) are considered inferior at best and enemies at worst. But when she goes off to college, she begins to question her beliefs, an ideological transformation she’s still working on when she joins with the rebellion in the last of the novel’s 600 pages. (It’s the first of a series; one hopes that Elloren will be more woke in book two.)

It was this premise that led Sinyard to slam The Black Witch as “racist, ableist, homophobic, and … written with no marginalized people in mind,” in a review that consisted largely of pull quotes featuring the book’s racist characters saying or doing racist things. Here’s a representative excerpt, an offending sentence juxtaposed with Sinyard’s commentary:

“pg. 163. The Kelts are not a pure race like us. They’re more accepting of intermarriage, and because of this, they’re hopelessly mixed.”

Yes, you just read that with your own two eyes. This is one of the times my jaw dropped in horror and I had to walk away from this book.

In a tweet that would be retweeted nearly 500 times, Sinyard asked people to spread the word about The Black Witch by sharing her review — a clarion call for YA Twitter, which regularly identifies and denounces books for being problematic (an all-purpose umbrella term for describing texts that engage improperly with race, gender, sexual orientation, disability, and other marginalizations). Led by a group of influential authors who pull no punches when it comes to calling out their colleagues’ work, and amplified by tens of thousands of teen and young-adult followers for whom online activism is second nature, the campaigns to keep offensive books off shelves are a regular feature in a community that’s as passionate about social justice as it is about reading. And while not every callout escalates into a full-scale dragging, in the case of The Black Witch — a book by a newcomer with a minimal presence online — the backlash was immediate and intense.

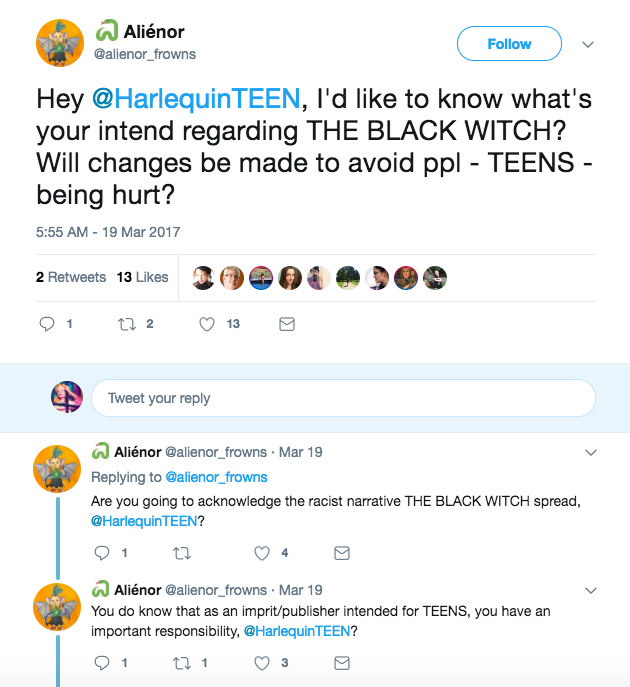

Based almost solely on Sinyard’s opinion, the novel became the object of sustained, aggressive opposition in the weeks leading up its release. Its publisher, Harlequin Teen, was bombarded with angry emails demanding they pull the book. The Black Witch’s Goodreads rating dropped to an abysmal 1.71 thanks to a mass coordinated campaign of one-star reviews, mostly from people who admitted to not having read it. Twitter threads damning the novel made the rounds, while a Tumblr post instructing users to “be an ally” and signal boost the outrage racked up nearly 6,000 notes. Sinyard kept a running tally of her review’s circulation; “11,714 views on my review of THE BLACK WITCH and .@HarlequinTEEN and .@laurieannforest have not commented,” she tweeted. (That number eventually swelled to 20,000.)

Positive buzz all but died off, as community members began confronting The Black Witch’s supporters, demanding to know why they insisted on reading a racist book. When Kirkus gave the novel a glowing starred review, dozens of commenters demanded a retraction; the uproar was so intense that Kirkus ran a follow-up essay by editor Vicky Smith on the difference between representation and endorsement: “The simple fact that a book contains repugnant ideas is not in itself, in my opinion, a reason to condemn it,” Smith wrote. “Literature has a long history as a place to confront our ugliness, and its role in provoking both thought and change in thought is a critical one.”

“Mimi” (not her real name), a teen book blogger with a follower count in the thousands and who describes herself as “a huge fantasy reader,” was among those who had been looking forward to The Black Witch — and she was initially thrilled to see Sinyard, an influential voice in the community, pick up the book. “I was really excited for what she was going to say about it. I thought it was going to be 600 pages of epic-ness,” she says. But her excitement soured when she caught wind of the book’s issues; just reading the sentences collected in Sinyard’s review and Twitter threads was painful, she says: “It hit me really hard. I’m so upset about it. It was very hurtful, and very, like, just harmful and triggering.”

The harm Mimi describes is central to campaigns like the one against The Black Witch, which are almost always waged in the name of protecting vulnerable teens from dangerous ideas. These books, it’s claimed, are hurting children.

But a growing number of critics say the draggings, well-intended though they may be, are evidence of a growing dysfunction in the world of YA publishing. One author and former diversity advocate described why she no longer takes part: “I have never seen social interaction this fucked up,” she wrote in an email. “And I’ve been in prison.”

Many members of YA Book Twitter have become culture cops, monitoring their peers across multiple platforms for violations. The result is a jumble of dogpiling and dragging, subtweeting and screenshotting, vote-brigading and flagging wars, with accusations of white supremacy on one side and charges of thought-policing moral authoritarianism on the other.

Representatives of both factions say they’ve received threats or had to shut down their accounts owing to harassment, and all expressed fear of being targeted by influential community members — even when they were ostensibly on the same side. “If anyone found out I was talking to you,” Mimi told me, “I would be blackballed.”

Dramatic as that sounds, it’s worth noting that my attempts to report this piece were met with intense pushback. Sinyard politely declined my request for an interview in what seemed like a routine exchange, but then announced on Twitter that our interaction had “scared” her, leading to backlash from community members who insisted that the as-yet-unwritten story would endanger her life. Rumors quickly spread that I had threatened or harassed Sinyard; several influential authors instructed their followers not to speak to me; and one librarian and member of the Newbery Award committee tweeted at Vulture nearly a dozen times accusing them of enabling “a washed-up YA author” engaged in “a personalized crusade” against the entire publishing community (disclosure: while freelance culture writing makes up the bulk of my work, I published a pair of young adult novels in 2012 and 2014.) With one exception, all my sources insisted on anonymity, citing fear of professional damage and abuse.

None of this comes as a surprise to the folks concerned by the current state of the discourse, who describe being harassed for dissenting from or even questioning the community’s dynamics. One prominent children’s-book agent told me, “None of us are willing to comment publicly for fear of being targeted and labeled racist or bigoted. But if children’s-book publishing is no longer allowed to feature an unlikable character, who grows as a person over the course of the story, then we’re going to have a pretty boring business.”

Another agent, via email, said that while being tarred as problematic may not kill an author’s career — “It’s likely made the rounds as gossip, but I don’t know it’s impacting acquisitions or agents offering representation” — the potential for reputational damage is real: “No one wants to be called a racist, or sexist, or homophobic. That stink doesn’t wash off.”

Authors seem acutely aware of that fact, and are tailoring their online presence — and in some cases, their writing itself — accordingly. One New York Times best-selling author told me, “I’m afraid. I’m afraid for my career. I’m afraid for offending people that I have no intention of offending. I just feel unsafe, to say much on Twitter. So I don’t.” She also scrapped a work in progress that featured a POC character, citing a sense shared by many publishing insiders that to write outside one’s own identity as a white author simply isn’t worth the inevitable backlash. “I was told, do not write that,” she said. “I was told, ‘Spare yourself.’

Another author recalled being instructed by her publisher to stay silent when her work was targeted, an experience that she says resulted in professional ostracization. “I never once responded or tried to defend my book,” she wrote in a Twitter DM. Her publisher “did feel I was being abused, but felt we couldn’t do anything about it.”

The only person I spoke with who agreed to be identified by her real name was Francina Simone, a self-published author and YouTuber who has disengaged from the YA community over what she sees as disrespectful and unproductive discussions about diversity. “They’re shouting at the people who already agree with them,” she says. “It sucks to say, but the fear is valid in that you will get dragged if you say, ‘Hey, maybe we shouldn’t tell this author to kill herself because one of her characters said something offensive.’” (Simone’s description is an exaggeration, but not by much. At the height of the pushback against The Black Witch, Forest was being derided as a Nazi sympathizer and accused of palling around with white supremacists, while those who questioned the tone of the discourse were rebuked for coded bigotry.)

The diversity-in-publishing debate is very much at the root of the outrage when it comes to campaigns like the one against The Black Witch, reflecting larger dissatisfaction with an industry that’s overwhelmingly white at just about every level. The multiyear push for more diverse books has yielded disappointing results — the latest statistics show that authors of color are still underrepresented, even as books about minority characters are on an uptick — and while the loudest critics demanded that The Black Witch be dropped by its publisher, others simply expressed exhaustion at the ubiquity of books like it. In a representative tweet, author L.L. McKinney wrote, “In the fight for racial equality, white people are not the focus. White authors writing books like #TheContinent or #TheBlackWitch, who say it’s an examination of racism in an attempt to dismantle it, you. don’t. have. the. range.” (McKinney did not respond to multiple interview requests.)

Still, the interpretation of Forest’s novel as a 600-page paean to anti-miscegenation seems rare among those who’ve actually read it. On Amazon, where the book is currently rated 4.3 stars out of 5, reviews generally agree that the book is firmly anti-prejudice, and that Elloren’s long slog in the direction of enlightenment is a realistic depiction of the process by which an indoctrinated person begins to expand her worldview. (There, the most common criticism is that the book’s message of tolerance is heavy-handed.) However, just reading a so-called problematic book in order to judge its offensiveness for oneself is considered by many to be beyond the pale.

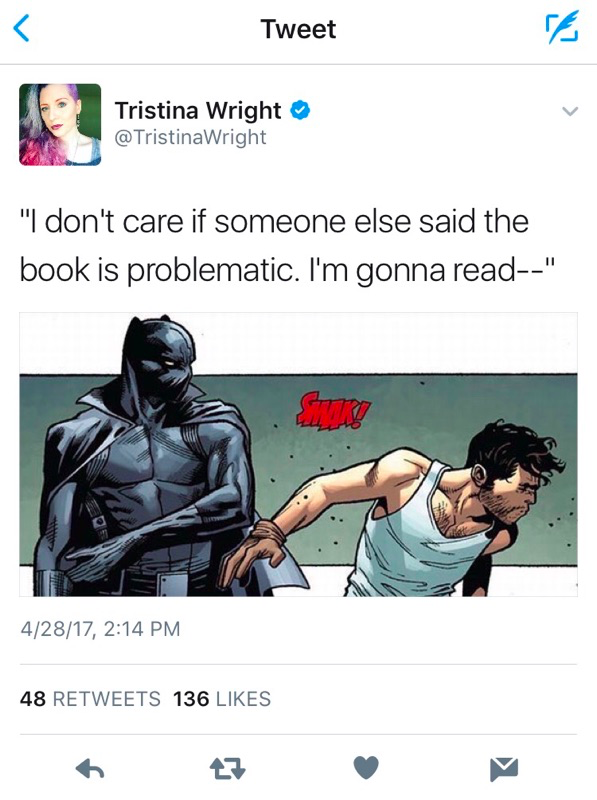

Author Tristina Wright was one of several who condemned would-be readers of called-out books, while young readers followed suit.

“Imagine being so privileged you care about your own entertainment more than the hurt of marginalized people,” one tweeted, while another declared, “Reading a book specifically because it’s been called out for racism doesn’t make you a champion of independent thought. It makes you racist.”

Mimi, the teen blogger who had once been so excited about The Black Witch, was among those who urged others to avoid the book, writing on her website and Twitter about the emotional pain it had caused her. She still hasn’t read it, and doesn’t plan to; she feels that Sinyard’s review tells her all she needs to know. “I trusted her take on it. She showed pictures from the book, and certain passages in the book, so it’s not like she was making it up,” Mimi says. And in the wake of the book’s release on May 2, Mimi is upset by the lack of response from Harlequin and galled by descriptions of the novel as pro-diversity and anti-prejudice. “I wanted the author and publisher to understand that there were people who were hurt by this,” she says. “But [Forest] says her book is for diversity, anti-homophobia, anti-racism, and it’s poking fun at all of us, like we did this all for nothing.”

For her part, Laurie Forest is aware of the protests, and cautious in how she talks about them. Responding to questions via email, she wrote, “My publishing house and I felt that it was important to listen to the discussion and we were respectful of people’s opinions and the debate. It’s a worthwhile discussion. Published books belong to their readers and readers should feel comfortable being honest about their views.” But she also says her book’s pro-diversity message is genuine: “I think there is a need for diversity in all phases of publishing, and it’s exciting to see that happening. The Black Witch explores what it’s like to grow up in a closed-minded culture, and its message is that people who may have been raised with prejudiced views can change for the better. But it takes time and education.”

Nevertheless, Mimi’s worry that the campaign against The Black Witch was “all for nothing” isn’t entirely off base. It’s rare that a title will be pulled in response to anger on social media. In August 2016, E.E. Charlton-Trujillo’s When We Was Fierce was yanked from shelves on the eve of its release amid accusations that it stereotyped its black characters; several months later, Harlequin Teen delayed YA fantasy The Continent after author Justina Ireland lambasted the book for employing white-savior tropes. But for the most part, those who spearhead the campaigns against problematic books seldom receive an official response.

Harlequin declined to comment for this piece, but another publisher at a big five imprint has a simple reason for staying out of the fray — “I truly don’t find those conversations of value, and I hope an author would feel the same” — as well as a message for readers like Sinyard who feel their campaigns deserve a response: “Get upset! I would say, continue to go get upset. It’s entirely your right. But if this were my author and we were having this conversation, I’d say, don’t respond, or block them. It’s not their position. It’s not their role. They are a reader. If they don’t like it, fine. As a publisher we are here to curate, defend, and protect fiction — the author’s ability to create as he or she feels fit, to tell the stories that he or she feels fit, and to not let the book be affected by outside opinion except those who are close enough to advise on story. “

As for the potential of these campaigns to affect a book’s sales, that same publisher is unconcerned. “There’s that line — there’s no such thing as bad press — and at some point people will buy it just to take a look at it so they can join the critical parade.” (Even The Black Witch, which took one of the worst online beatings in recent memory, scored a No. 1 rating in Amazon’s department of “Teen & Young Adult Wizards Fantasy” a few days after its release and has been overwhelmingly well-reviewed since.)

Among the book-buying public, though, that parade may be mostly passing unnoticed. The scandals that loom so large on Twitter don’t necessarily interest consumers; instead, the tempest of these controversies remains confined to a handful of internet teapots where a few angry voices can seem thunderously loud. Still, some publishing professionals imagine that the outrage will eventually become powerful enough to rattle the industry. Another agent, who describes himself as devoted to diversity in publishing since before it became a mainstream concern, is ambivalent about the current state of affairs.

“I think we’re in a really ugly part of the process,” he says. “But as we’re trying to encourage a greater diversity of readers and writers, we need to be held accountable for our mistakes. Those books do need to get criticized, so that books which are written more mindfully, respectfully, and diligently become the norm.”

It’s also a process in which tough questions lie ahead — including how callout culture intersects with ordinary criticism, if it does at all. Some feel that condemning a book as “dangerous” is no different from any other review, while others consider it closer to a call for censorship than a literary critique. Francina Simone, for one, falls firmly in the latter category. “People seem to want these books to validate them, and that’s almost completely impossible,” she says. “It would be like me watching The Simpsons and saying, ‘It’s harmful to me, take it off the air.’ It’s baffling. People pretend as if there is no off switch. [The idea] that it shouldn’t be in the public atmosphere — I find it extremely funny that people don’t think that’s censorship.”

And even if it becomes an article of faith that certain books are harmful and shouldn’t exist, how to adjudicate the claims of harm is a question nobody seems able to answer. During our conversation, the ambivalent agent suggests that Twitter shaming is called for “when someone is resistant and won’t acknowledge when they’ve clearly made a mistake,” but hedges on the question of who gets to decide what a clear mistake looks like, or when an authorial decision is a shaming-worthy offense:

“I don’t have an easy answer to that. The problem with these sorts of conversations and debates online is that as soon as an accusation is made, the burden of proof is put on the accused party. You can make all sorts of allusions to The Crucible. I don’t know what needs to be done. I’m certainly not happy with how it plays out.

“But,” he adds, “I don’t think the answer is to have everyone shut up and not criticize it.”

Twitter being Twitter, that outcome seems unlikely. In recent months, the community was bubbling with a dozen different controversies of varying reach — over Nicola Yoon’s Everything Everything (for ableism), Stephanie Elliot’s Sad Perfect (for being potentially triggering to ED survivors), A Court of Wings and Ruin by Sarah J. Maas (for heterocentrism), The Traitor’s Kiss by Erin Beaty (for misusing the story of Mulan), and All the Crooked Saints by Maggie Stiefvater (in a peculiar example of publishing pre-crime, people had decided that Stiefvater’s book was racist before she’d even finished the manuscript.)

But in an interesting twist, the teens who make up the community’s core audience are getting fed up with the constant, largely adult-driven dramas that currently dominate YA. Some have taken to discussing books via backchannels or on teen-exclusive hashtags — or defecting to other platforms, like YouTube or Instagram, which aren’t so given over to mob dynamics. But others are pushing back: Sierra Elmore, a college student and book blogger, expressed her frustration in a tweet thread in January, writing, “[Being] in this community feels like being in high school again. So much. No difference of opinion allowed, people reigning, etc… I and other people I know (mostly teens) are terrified about speaking up in this community. You don’t get a chance to be wrong here.”

And if YA changes, it may well be at the behest of the young adults themselves, especially when even the community’s crusaders for social justice seem weary of the constant conflict. When asked if she’d have anything to say to the people who thought The Black Witch was a worthwhile and critical take on the dangers of prejudice, Mimi sighs.

“I’m open to having a discussion with someone like that. But sometimes in the twitterverse, people let their tempers run.”