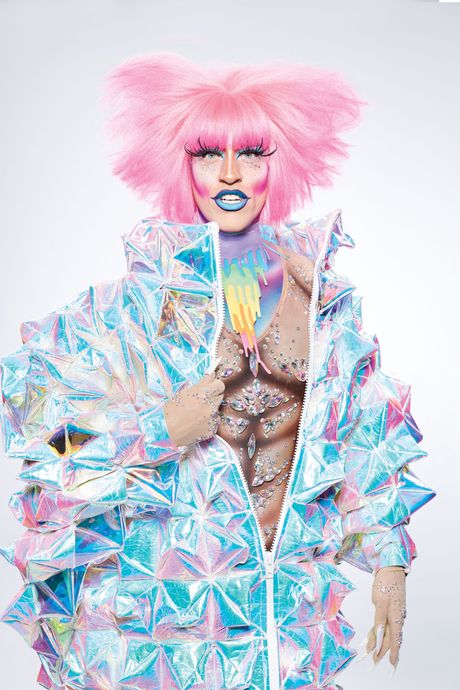

Oh, hennnnnny: America loves its drag queens. Moms do, kids do, your local gay bars do. Even McDonald’s does. From the cast of the blockbuster remake of A Star Is Born to the pink carpet at the Met Gala — not to mention the millions around the world who’ve tuned in to RuPaul’s Drag Race for the last decade — what was once a glittery subculture on the edge of gay culture has become one of our global pop preoccupations with its own hierarchy of stars and story lines for the fans to get behind, marketing deals and Billboard chart-toppers. It’s become a very big business with its own star-power machinery attached. It’s become almost unavoidable. Their job is to make sure of it.

Ten years ago, it wouldn’t have been possible to make this list of the country’s most powerful drag queens. There were drag queens scraping out a tinseled living all over the country, playing dance clubs and gay-pride events. RuPaul Andre Charles, the self-styled “Supermodel of the World” (as his 1993 debut album named him), had all but created the mainstream-famous drag queen for the modern era, but he was about it. Then came RuPaul’s Drag Race, the reality competition, which yanked drag from the periphery and not only returned RuPaul to stardom but gave contoured, breast-plated birth to some 140 new little novas.

The show, in its star-making efficiency, has become like the Motown of drag, with Ru in the visionary role of Berry Gordy. And he has no problem with taking credit for this revolution in a wig.

“Bitch, are you really serious?” He laughs. “Our show is being seen around the world and it’s introduced drag to people who have never even heard of it. Before that, drag was in the subversive clubs. In fact, even in clubs, it was in a place where it wasn’t celebrated. Around the time that our show went on the air, there was nothing. Girls were performing at restaurants without even a stage. Without even proper lighting.”

The show grew slowly in its bootstrapped first seasons, and then it jumped onto Netflix, which streams it across the globe, and moved from Logo, the niche gay network on which it originally aired, to VH1.

“When we took over, we said this gem has real potential,” says Chris McCarthy, the president of MTV, VH1, CMT, and Logo, who presided over the move. “We were ahead of culture and culture has finally caught up.”

Now drag queens walk your high-fashion runways and appear in your Prada campaigns. They perform for Beyoncé. They DM with Rihanna. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez gushes and mourns on social media. (She also, in the idiom of the show, instructed Democratic presidential hopeful John Delaney to “sashay away.”) Nancy Pelosi went one better, visiting the Werk Room during an episode last year. You can study Drag Race at college (the New School offered its first course in the show this spring) or wear it to junior high (Hot Topic sells merch featuring several of the Ru girls). Many of its queens, winners, and also-rans alike endorse products or companies on their social-media channels, and now the largest among them star in McDonald’s ads, too.

“Certainly in the past year or two, major corporations seem far more comfortable with drag than they’ve ever been,” says Randy Barbato, the co-founder of World of Wonder, the production company that makes Drag Race and its satellites, RuPaul’s Drag Race All Stars and Untucked.

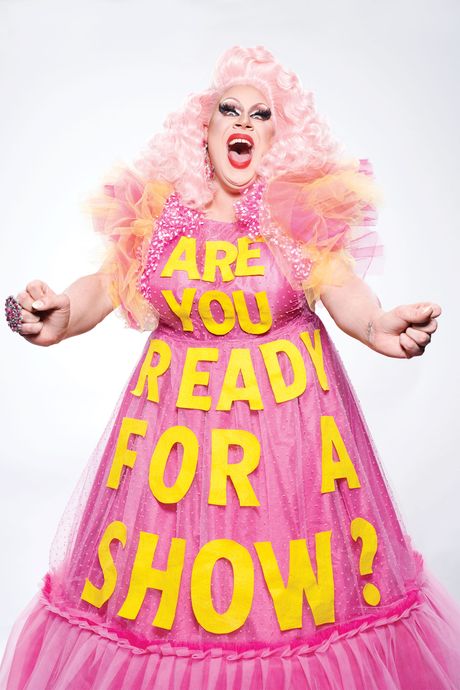

So does the public, which gathers to worship their drag heroes just as Marvel fans dress up for Comic-Con and Jets fans hit the tailgate at MetLife Stadium. Biannual DragCons, in New York and L.A., draw tens of thousands of guests: 50,000 in L.A. this year. Nor are they all gay men. Most attendees do not identify as gay, Barbato says. At the 2018 events, the most recent for which data is available, over 55 percent were women and more than half under 30.

“It is the most beautiful thing in the world. It’s every flower in full bloom,” RuPaul says. “We’re talking straight, gay, black, white. We’re talking 8-year-old kids and 75-year-old women. We’re talking everybody. It’s a city of beautiful flowers. A utopia. They are loving it.”

But you don’t have to go to DragCon. Drag can come to you, whether you like it or not. It’s there in a new shared vocabulary, gentrified out of the gaydom (in particular, gay communities of color) and into your cubicle mate’s vernacular. The tea is spilled everywhere now.

With its all-but-certain 12th season (and fifth of All Stars), Drag Race will have lasted more seasons than The Carol Burnett Show, as Zaldy, who designs RuPaul’s gowns for the show and won two of the show’s nine Emmys in the process, pointed out recently. “Our little drag show has become a cultural phenomenon,” the man in those gowns said from the stage of the Orpheum Theatre during the winner-crowning finale of the 11th season of Drag Race last month, addressing “the millions of fans watching on VH1 and around the globe.”

As was perhaps inevitable — and in its way, a confirmation of the show’s success — the cagier wing of the conservative party is already sounding the alarm. Sohrab Ahmari, the New York Post op-ed editor, inveighing against the scourge of drag-queen story hour at the local public library, has declared that the time for polite protest has passed. What started as a Twitter fulmination eventually devolved into a pile-on about the culture wars, with The Federalist warning that “The Cultural White Walkers Have Descended.”

It is tempting to think of this as the death rattle of an eroding opposition, the last gasps of the terminally humorless. RuPaul has always been aware of the terror inspired by a man in a wig — particularly a black man, particularly a blonde wig — in those of shakier constitutions. “Every time I bat my eyelashes, it’s a political act,” he told The New Yorker in 1993, riding high on the success of Supermodel of the World and a nascent career as a dance-pop diva. Looking back at RuPaul’s career from that time, and how he broke into the mainstream after years of success in the clubs, one is astonished at how unchanged his spiel is. Many of the maxims that rouse amens from the Drag Race stage today were already scripture 25 years ago. RuPaul has never been small. It’s the pictures that got big.

So, no, RuPaul is not surprised by the show’s success. “I know that inside of every human being there’s a child that loves colors and sparkly things and things that are exciting. Also inside of every one of us there is the knowledge that we are all in drag. Now, whether humans can articulate that or not is neither here nor there.” Therein lies the rub. People are fickle, as Ru himself admits, “and especially fickle when it comes to concepts of men and femininity. I’ve seen men in my lifetime put the kibosh on that behavior overnight.”

If there’s a reason to think this time is different — and there just might be – it is that this time, it’s not just Ru. With the dozens of queens Drag Race has elevated, promoted, and sent touring the world, he has brought the cavalry.

Selection for Drag Race is not a onetime boost. Winning means a $100,000 cash prize, but win or lose, performers can go on to have the kind of careers that net as much as $1 million a year. Making it onto the program means induction into a sorority of increasingly professionalized entertainers, a sisterhood of the traveling panties.

“They’re out there,” Barbato says. “The more you have in the marketplace, and the more they are working, the more of a long-tail thing it is.”

“That’s what I’m most proud of,” Ru says. “Creating a platform for these fabulous performers to launch a career that spans the globe. They’re out there working right now, and they’re making really, really big bucks doing it. They literally are getting rich. And I fucking love that.”

Frankie Sharp, a New York events producer who has had Drag Race alumnae at his parties at bars like Metropolitan, Dream Downtown, and 3 Dollar Bill, confirms this. “I’ve worked with most of the girls from New York before and after the show,” he says. “It can make someone’s booking fee increase sometimes by 60 times over. I’ve seen it take one drag artist I know from poverty to an apartment in Gramercy.”

As they filter into the world and get a piece of it, so does RuPaul, who is testing a daytime talk show — out of drag but along drag principles, he said — on Fox stations in seven markets beginning June 10. A U.K. version of Drag Race is coming to the BBC. Ru has ascended to sage status: from one who was Lettin’ It All Hang Out (the title of his 1995 autobiography) to a GuRu (his 2018 follow-up).

But as the show settles into its groove — a groove maybe even too comfortable — Drag Race can begin to seem the victim of its own success, exhausted by its own inescapability. Even Ru sometimes seems a little bored. But then there are the new Drag Races with their promise of the new: World of Wonder has licensed the show format in Chile and in Thailand, which in particular brings pyrotechnics and passion that have reinvigorated interest among die-hard fans.

Some in the drag scene complain that Drag Race’s success has given it has a monopoly on star-making, cutting off the club circuit and elevating its own version of drag above all others. “Who is good at Drag Race is equated to who is good at drag,” a queen named Charlene carped to the Times last year. Contestants often audition over and over before being selected, and Sharp says he has seen rifts between those who are selected and those who aren’t. “That show can really get the girls riled up,” he said. “That’s what happens when something this powerful changes the culture.”

But in general, the rising tide has lifted all boats. “As big as drag feels right now, we still have a long way to go,” David Charpentier, the founder of Producer Entertainment Group, which represents many of the show’s alums, told Billboard. “The plan for us and a lot of these queens is global domination.”

“We’ll be looking at how do we spin this out,” McCarthy says. “How do we turn it into other franchises?”

*A version of this article appears in the June 10, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!