Don’t mistake Trina Robbins’s gentleness for shyness. There have been many comic books with all-female creative teams since the 79-year-old writer-artist-editor came up in the “underground comix” scene of the late 1960s and early ’70s. She’s overjoyed for their success. But she wants you to know exactly where she, and the 1970 comics anthology she spearheaded, fit into history.

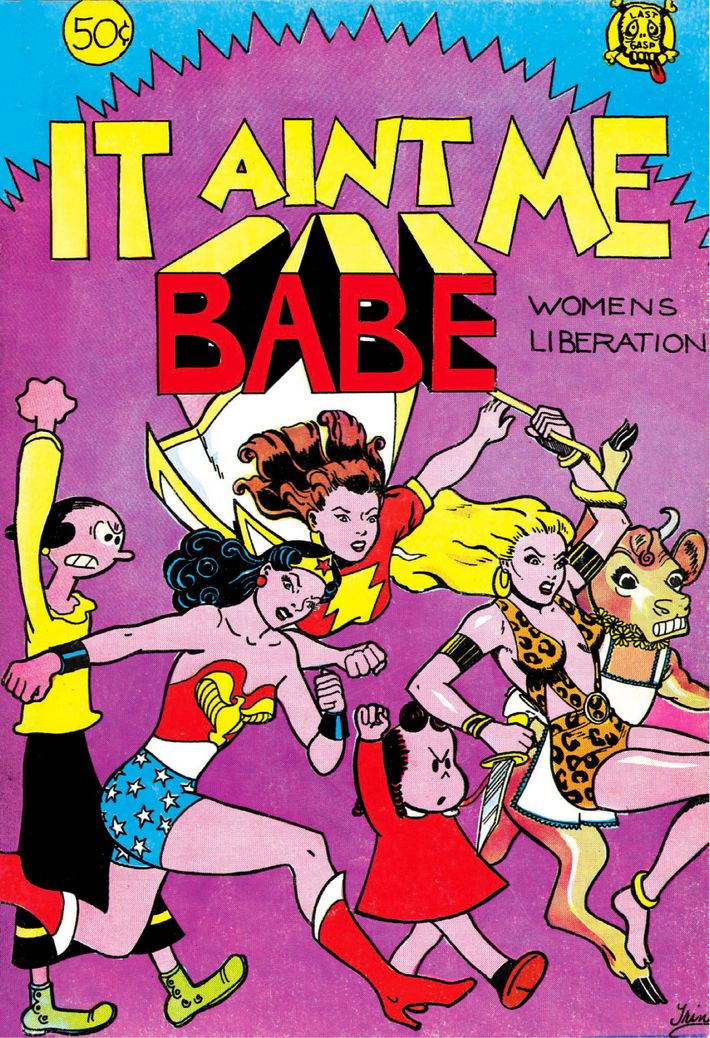

“We produced It Ain’t Me Babe Comix, which is the very, very, very first all-woman comic book,” she told an audience at the San Francisco Public Library a few years ago. “And I stress this because, a couple of times, people have written about me and it’s like they’re hedging their bets, and they say, ‘And she produced one of the first.’ Well, y’know what? It’s not ‘one of the first.’” Her voice dropped down a quarter-octave. “It’s the fucking first.”

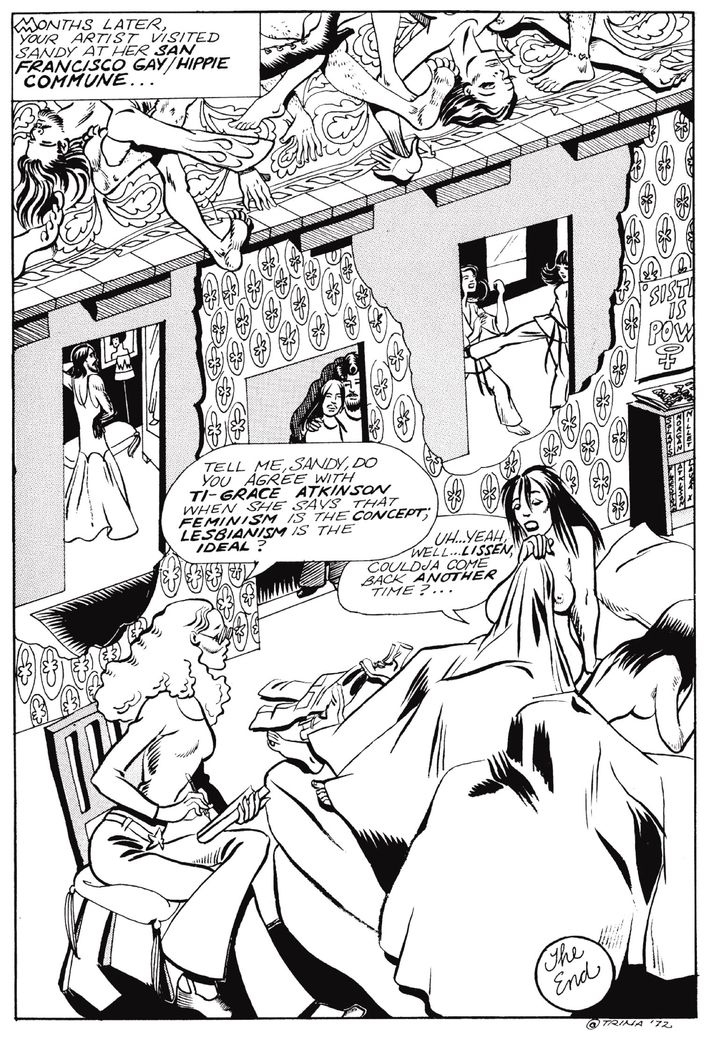

And that comic wasn’t the only instance in which Robbins helped shape the development of comic books and the way we perceive women in them. Just two years later, she helped launch the longest-running comics series created and edited entirely by women, Wimmen’s Comix. On top of that, in its first issue, she wrote and drew a short story called “Sandy Comes Out,” which starred the first extant lesbian comic-book character outside of pornography. Later, she became the premier historian of female comics creators, penning one prose book after another on the topic. The women she writes about managed to carve out niches in the boys’ club that is the American comics industry — an achievement she shares with them.

If you haven’t heard of Robbins, it’s in no small part due to the fact that the comics ecosystem has historically been uninterested in feminist rhetoric and female achievement. That’s changed to a significant degree in the past decade, which has seen more and more outspoken women creators rising in the ranks. But Robbins was their distant forerunner. Her time in the underground was rarely a smooth ride, and the bumps along the way were sometimes created by her tendency to advance a version of feminism that both inspired and rankled those around her in that underground.

Robbins’s awakening came when she’d already built a remarkably unusual life. Born Trina Perlson in Queens in 1938, she spent her childhood fixated on any comic she could find with a female protagonist and started drawing, first for herself and then for sci-fi fanzines. Suffering from chronic low self-esteem, she dropped out of Queens College and moved to Los Angeles in the early ’60s to work as a nude model for magazines. She married a magazine impresario named Paul Robbins, who got her out of the girlie-mag business, and she proceeded to become a part of the the L.A. rock and folk scene, designing clothes for musicians — and, oddly enough, becoming the “Trina” of Joni Mitchell’s “Ladies of the Canyon.”

By 1966, she was a full-on hippie and moved to downtown New York City after having a vision in which her father died. She founded a clothing boutique there called Broccoli (so named due to a drug trip in which she thought she could communicate with the vegetable) and started drawing trippy comics in the form of ads for the store in alternative paper The East Village Other. In 1969, she got published in her first comic book as part of the nascent underground-comix movement, a loose collective of creators (some of the best-known include R. Crumb and Art Spiegelman) and publishers who specialized in boundary-pushing printed stories. Her thick-inked contributions to the movement tended to be more abstract than obscene, and by the time she decided to leave Paul, arrived in San Francisco in 1969, and joined up with the booming underground scene there, she had built a growing reputation for herself.

But 1969 was probably most remarkable for Robbins not due to her creative output, but rather her reading material. She came across an article headlined “WHY THE WOMEN ARE REVOLTING” in an alternative newspaper called The Berkeley Barb and transformed from an effervescent hippie into an ardent second-wave feminist. It’s hard to overstate how much this transition changed Robbins. Patrick Rosenkranz, a longtime chronicler of the underground movement, tells me he, later in life, checked a quote with her while preparing a book and she replied, “I never said that.” “Well, fortunately I had all my transcripts, so I sent it to her and showed it to her,” he says. “And she said, ‘Well, that was before I was in women’s liberation. I don’t feel that way anymore.’”

What she did feel at the time was left out. She attempted to fall in with the comix crowd in which her boyfriend, underground creator Kim Deitch, had become a star. It didn’t exactly work, and Robbins is certain that it was because she was a woman. Though she was able to get work published in outlets like the groundbreaking feminist newspaper It Ain’t Me Babe, she was rarely asked to contribute to actual comic books, which were all edited by men. And there was social exclusion too: Robbins recounts in her 2017 memoir Last Girl Standing that Deitch “would receive party invitations in the mail, addressed to Kim Deitch, never to Kim Deitch and Trina Robbins.” When she did get into events, she writes that they could be sexist nightmares. One dinner gathering allegedly involved “the guys going from room to room, trying to get away from me, and me following. The vibe was clear: why isn’t this bitch in the kitchen where she belongs?”

What’s more, she felt that the work these men were producing was increasingly awful in its depictions of women. For example, in her memoir, she cites Crumb’s 1970 comic “Underground Hotline,” in which the artist imagines himself strangling a female TV interviewer who calls him out on the “sick stuff” he draws. “I think that a lot of these guys simply were misogynist,” she tells me. “It turned out what a lot of these guys, what they had in their head was very vicious stuff, very violent stuff.”

Whether or not the work of Crumb and his ilk was, indeed, misogynist is a matter of much debate and won’t be resolved here. With any analysis of Robbins comes the question of why, exactly, she never totally fit in with the undergrounders. On one hand, no one can deny that the underground was male-dominated. On the other hand, there are some who were there who say Robbins’s primary problem wasn’t structural sexism, but rather her art, personality, and politics.

When I ask collaborator Barbara “Willy” Mendes whether she agrees with Robbins about the no-girls-allowed aspects of the scene, she replies, “I don’t think that I think it was as sexist as it was …” She trails off for a moment, trying to be careful in her words about her friend, then concludes, “I think, for me, it wasn’t.” Rosenkranz says Robbins wasn’t invited to contribute to many comic books “because she wasn’t good enough.” Underground cartoonist Diane Noomin says Robbins “had sort of a queen-bee approach to feminism” and that “there were a lot of people who were afraid of her.”

Whatever the reasons for her marginalization, she didn’t allow it to stop her from being bold. Though her artwork from the period remains alluring and distinctive, her most important underground legacy is the work she did behind the scenes. In 1970, she and Mendes put together and edited It Ain’t Me Babe Comix (named after, though not directly affiliated with, the paper), a single issue filled to the brim with female-led stories and joyous feminist advocacy. It was the first comics anthology exclusively made and edited by women, and thus an oft-unsung turning point in the history of comics art — “a terrain-shifting move,” as comics historian Hillary L. Chute puts it to me. Robbins followed that up with 1971’s all-woman anthology All Girl Thrills and a solo comic called Girl Fight Comics in 1972.

But that was all, in a way, a prelude to the longest-lasting of the projects Robbins helped get off the ground: Wimmen’s Comix. Founded in 1972 after publisher Ron Turner asked Robbins’s compatriot Pat Moodian to put together a women’s-lib comic, it went on to become the most significant all-woman comics series of the next two decades. It was also the source of what was perhaps her most momentous artistic conflict.

Robbins was deeply involved in the publication from the very beginning as a contributor and leader. We should be delicate about that latter term, though, as Wimmen’s Comix was designed to be as egalitarian as it was feminist, with a rotating editorship for each successive issue. Flip open the early issues and you’d find a dizzying range of stories that deal with womanhood in one way or another. It had everything from the social realism of Lora Fountain’s “A Teenage Abortion” to the weed-fueled high fantasy of Sharon Rudahl’s “Tales of Sativa,” as well as Robbins’s aforementioned, groundbreaking “Sandy Comes Out,” which was — oddly enough — inspired by the coming-out of R. Crumb’s sister Sandy. The anthology would go on to feature the work of cartooning giants like Alison Bechdel and Melinda Gebbie, always striving to push boundaries and raise feminist awareness.

But all was not well in the revolution. Wimmen’s Comix also featured the debut of one cartoonist who would become Robbins’s loudest critic: Aline Kominsky, now Aline Kominsky-Crumb. She had a style that couldn’t have been more different from that of Robbins. Where the latter was fond of refined elegance in content and presentation, Kominsky was committed to radical messiness. Kominsky’s stories for Wimmen’s Comix were autobiographical affairs that depicted, in uncomfortably vivid detail, her own self-hatred and neuroses. Robbins wasn’t a fan of the work, but she was even less keen on Kominsky’s decision to date R. Crumb. Kominsky and Noomin grew resentful of Robbins.

“[W]e were feeling increasingly annoyed and alienated from the group, especially from Trina Robbins and her minions,” Kominsky wrote of herself and Noomin in her 2007 graphic memoir Need More Love. “We unabashedly liked men. We liked being sexy, and felt our Female Power to be a positive force … We also started looking at Trina’s and Sharon Rudall’s [sic] work more critically, and concluded that it was shallow, childish, simplistic, and humorless. We were more comfortable seeing ourselves as ‘Bad Girls,’ sluts, anarchist artists doing whatever we pleased.”

The resentment was — and is — mutual, though Robbins thinks it has less to do with politics than personalities. “I think they just don’t like me and just never liked me,” Robbins says. “I think it’s as simple as that.” Whether or not that was true at the outset, Robbins certainly gave them reason for bitterness in time. In April of 1975, a fateful article was published in the Barb, written by a woman named Sally Harms, ostensibly about sexism in the underground-comix scene. But the key passage was a bit of spite in which Robbins was quoted as saying Kominsky and Noomin were “camp followers” (an archaic term for women who sexually serviced men in the military) that “[t]heir work is obviously crude,” and that “I’ve already rejected work that’s better than theirs.” Kominsky and Noomin had enough. They set out and formed their own all-woman comic, Twisted Sisters.

“We didn’t like Trina’s definition of feminism,” Noomin tells me. “We were more interested in irony and self-deprecation and autobiographical stuff than presenting idealized Amazons who looked like Sheena of the Jungle. It was kind of a difference of opinion.” Says Rudahl, “It wasn’t any kind of deep-seated philosophical artistic split. It was just plain jealousy, and that was typical high-school, bad-girl stuff.” Whatever the cause, the split rocked the underground. “Unfortunately, it seemed to force some of the other women in that collective to take sides,” recalls publisher Denis Kitchen, who had been one of the few men to invite Robbins into his comics. “I think I thought initially, Well, it’ll fly over, and it didn’t.”

Robbins was criticized from the left flank, as well, on the grounds that Wimmen’s Comix didn’t include enough work from queer women and women of color. “We reached out to all women in our comic; we always asked for submissions,” Robbins says, but “we just never got anything from women of color” and “there really wasn’t much we could do until we finally got a submission from a lesbian.”

None of that should overwrite the impact of the work Robbins and her comrades made in the underground. Nor should historians forget Robbins’s subsequent work after the underground scene petered out in the late 1970s. She went on to edit the all-woman erotica comic Wet Satin and contribute to the transgressive French anthology Ah! Nana. She completed acclaimed graphic novels like 1981’s Dope and 1985’s The Silver Metal Lover. She even did a brief stint on DC Comics’ Wonder Woman, becoming the first woman to draw a Wonder Woman comic (a bittersweet landmark, given that it took four-and-a-half decades of the character’s existence for that to finally happen). Perhaps most important for long-term posterity are her excavations of female comics creators like Ethel Hays and Edwina Dumm in her books on the subject, the most recent of which is 2013’s Pretty in Ink.

Throughout it all, she has remained a firebrand. “Any time there was talk about integrating the industry more or getting comics to girls, that was Trina’s crusade,” says comics journalist and editor Heidi MacDonald. She would speak out on behalf of women creators past and present and help organize campaigns to promote them. As MacDonald puts it, “She didn’t want to be alone, didn’t want to be the only woman in the room.” She stopped drawing comics in the early 1990s due to a bout of depression and, according to her, the fact that people ceased inviting her to draw. But she has continued to write comics and prose. Just last year, in addition to publishing Last Girl Standing, she also put out an adaptation of a Yiddish short-story collection her father wrote in the late 1930s, illustrated by 15 different artists. At one point in our conversation, she draws a comparison between herself and Hilda Terry, a cartoonist she’s written about, who died at her computer at the age of 93: “That’s how I want to go,” she says.

And Robbins thinks the world is finally catching up to her and her aspirations. Though there are still many mountains to climb, women and gender issues are more prominent in the comics world than they’ve ever been, with a bevy of female writers, artists, and writer-artists working on everything from superhero series to autobiographical webcomics. “I used to be a voice crying out in the wilderness, you know?” she says. “I’m not anymore. There are all of these women. They’re so talented. They’re so smart.” That could be the end of the statement, but Robbins can’t resist just a little bit of self-congratulation: “They all think like me.”