“Not too many people draw black people as well as I do,” the (white) comic book artist Neal Adams says with a smile. Ensconced behind a drawing board in his Manhattan studio, clad in his trademark incompletely buttoned dress shirt and loose tie, Adams is in the midst of recalling the creation of one of his most famous pages. In fact, it’s one of the most notable pages in the history of the American comic book: a scene from 1970’s Green Lantern No. 76 in which an elderly black man accosts the white superhero Green Lantern for being insufficiently attentive to the concerns of people of color.

The page is a deceptively simple collection of words and pictures that, thanks to Adams’s art and writer Dennis O’Neil’s script, altered the course of the superhero genre. Green Lantern — civilian name Hal Jordan — is a human who was long ago drafted into an intergalactic police force by cyan-colored aliens and spends his days battling cosmic villains and palling around with fellow members of the Justice League. That isn’t enough for his accuser, whose wrinkled face is so energized that it spills over from the second panel to the third.

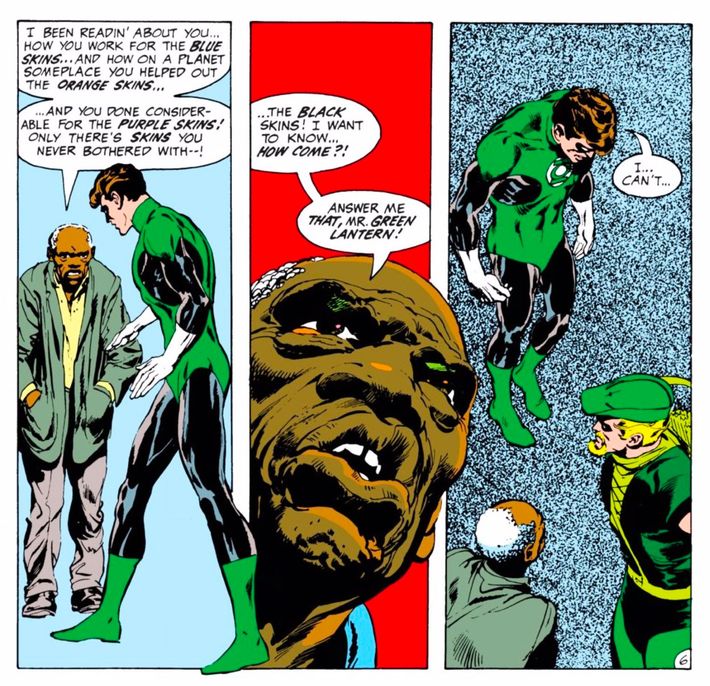

“I been readin’ about you,” he tells GL. “How you work for the blue skins … and how on a planet someplace you helped out the orange skins … and you done considerable for the purple skins! Only there’s skins you never bothered with — the black skins! I want to know … how come?! Answer me that, Mr. Green Lantern!” Adams, an expert in human anatomy, slumps Hal down in the final panel; O’Neil gives the hero a pathetic response to the man’s query: “I … can’t …” No one had played with the dynamite sticks of black dissatisfaction and white guilt like this in the genre before. To put it in contemporary terms, this was the moment superheroes got woke.

At the time, Green Lantern sales had been down in the dumps, and this page helped turn its fortunes around, launching the series to acclaim and unprecedented mainstream media attention. Adams is proud of the page’s message — and just as proud of his draughtsmanship. “People were taught to draw white people and call them black people because they drew their hair a little kinky,” he says. “But that guy is a black guy. You have to draw black people different just like you have to draw Asians different. People are different from one another. That’s what makes the world good. That’s what makes the world great.”

O’Neil is significantly less sentimental when I ask him over the phone to recall his role in making the page. For him, the creation of the now-famed moment was largely business as usual. “We had our tool kits together, we knew how to do this work, and I don’t know how Neal approached it, but for me, this was something that I always kept in mind: it is my job,” he says. “I don’t have the luxury of waiting for inspiration, which probably will never come.”

Therein lies the dichotomy that powered the creation of a great little piece of the comics canon. Its artist thought he and his partner had turned a low-selling series into something revolutionary. But to its writer, it was just another day at the office. They’re both right: For two of the most dynamic creators to ever operate in the medium, simple workmanship was anything but simple.

Both men were liberals who grew up without black people in their orbit. O’Neil was born to an Irish-American family in 1939 and reared in St. Louis. “I lived in an all-white neighborhood, and Irish Catholics do tend to occasionally be guilty of bigotry,” he says. “One of my relatives would turn off the television when there was a black performer on a variety show: ‘Really, they shouldn’t allow them on. Y’know, they don’t have souls!’ That was the kind of background I came from.”

Adams, a Jewish Brooklynite born in 1941, recalls thinking he wasn’t prejudiced until he saw the city beyond his native Coney Island: “I pretended that I was liberal, I pretended that I understood,” he says. “And then you’d go through Harlem and it’s, ‘What are you doing here, white boy?’ And how did that happen? Excuse me, you’re just another guy, right? But you happen to have darker skin and you’re treating me like I put you there. And guess what? I did. I did put you there. That was the reality.”

The industry they ended up in wasn’t a whole lot better in terms of diversity. At the dawn of the ’70s, comics was still primarily a white man’s game. There had been talented black and mixed-race creators over the years, but they were very much the exception, and there wouldn’t be a full-time black superhero comics writer until the early 1980s. Depictions of black people on the page were also lacking. Sure, you had the hypercompetent Black Panther, but he didn’t even have his own series. More often than not, if you saw someone with dark skin in a superhero title, they were a random street tough. On the rare occasions when creators addressed racism, it was in simplistically Manichean terms: the good guys virtuously spouted generic up-with-people rhetoric and the racists were sinister hatemongers like, well, Hate-Monger, a Marvel Comics villain who was literally Hitler.

O’Neil wanted to do something different, and Adams was right behind him. But that doesn’t mean they were friends. Indeed, this now-legendary duo hardly ever met. The two freelancers had been paired up on DC Comics’ Batman-starring Detective Comics to considerable acclaim, but their alchemy happened without contact. “I wrote scripts, and I turned them in to [DC editor] Julie Schwartz, and they disappeared into that black hole of the printing process,” O’Neil recalls. “Julie edited them, he gave them to Neal, and they took it from there.” Nevertheless, they were a hot item, though O’Neil was skeptical about how long the ride would last. “We were the flavors of the week — a characterization Neal would disagree with,” he says.

Here’s where the narrative gets a little dicey. According to Adams, the Green Lantern revival was his idea. He says he wanted a crack at the emerald-shaded super-gent to prove his mettle. The series had, until recently, been drawn by one of the great artists of the era, Gil Kane. “I thought that I could at least take a shot at doing something as good as Gil Kane did,” Adams recalls. “So I thought Green Lantern, of the characters at DC Comics, was the best possibility for really expressing yourself artistically.” The scribe’s version is much more prosaic: O’Neil says Schwartz (who died in 2004) just “had a soft spot” for GL and wanted a Hail Mary attempt at reviving sales for the character’s series, so he recruited the two rising stars.

Whatever the specific chain of events, Schwartz assigned both men to the ailing series and awaited the results. O’Neil mulled the title character over and came to a realization about his essence. “My take on Green Lantern was, he was a kind of cop,” he recalls. “He was, in his own way, an Establishment character. I mean, he wore a uniform, he did what he was told, he answered to bosses.” But in order to explore that idea, “I needed somebody to take the opposite point of view,” he says.

Enter Green Arrow, DC’s other lime do-gooder. Created in 1941, he’d typically been depicted as something of a Batman rip-off: an un-superpowered billionaire playboy with a sideline as a crime-fighter, albeit one who used a bow and arrow. However, Adams had given Arrow — civilian name Oliver Queen — a visual makeover in a series called The Brave and the Bold the previous year and O’Neil had made him lose his fortune in an issue of Justice League soon after. Oliver was, all of a sudden, putty in the two creators’ hands. “I could do with his personality whatever I felt needed doing,” O’Neil says. “So I went with him representing people who are closer to the left, and Green Lantern representing the good conservatives.”

But how would he explore that notion? He chose to pick a topic that was literally close to home. “I was living in a slum,” O’Neil says. He was dwelling in the hellscape that was 1970s downtown Manhattan and chose to have GL and GA encounter urban poverty — particularly black poverty — up close. That said, when I ask him if he felt some kind of progressive fervor while hammering out his story, he demurs. “What that story’s about is something that concerned me as a husband, father, et cetera, et cetera, but at some point, you just sit down and do the job,” he says. “I met the deadline, I got the story in on time, and went to work on the next one.”

By contrast, when Adams received O’Neil’s script, he was enraptured. “It was great. I couldn’t believe it,” Adams says, shaking his head with wonder, even now. “It was a fresh, new view. A story between two men who are politically opposed to each other and morally dysfunctional and fighting, and in effect, letting them fight it out.” He was particularly impressed with how it interrogated the deficiencies both of liberal and conservative viewpoints in the form of the characters: “There was nothing wrong with either one of them at their base, but along the way they had acquired some awfully bad attitudes.” It was decided that the cover of the issue would feature both heroes’ names in equal size, making the issue the first in a run on Green Lantern that is colloquially known as Green Lantern / Green Arrow. Adams got to work.

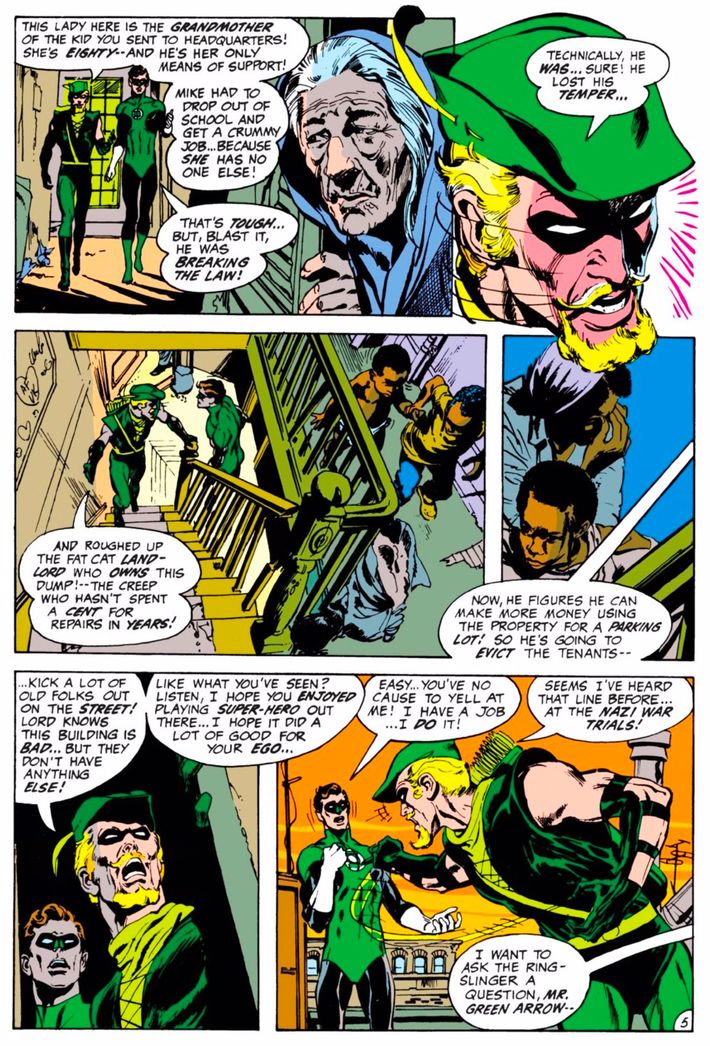

The finished product is as charmingly quaint as it is bluntly didactic. The opening page shows GL soaring through Green Arrow’s native Star City, as narration informs us, “often he has vowed that ‘no evil shall escape my sight’” but that, ominously, “he has been fooling himself. ” He sees some ruffians beating up a rotund, besuited white man on a street and uses his magic ring to send them to police headquarters. To his surprise, people start pelting him with garbage. GA suddenly appears and tells GL to back off. “Green Arrow,” Hal says. “You’re … defending these … these anarchists?!”

Oliver informs Hal that the man the latter rescued on the street was, in fact, Jubal Slade (what a name!), the local slumlord, who’s planning to tear down a tenement in order to set up a parking lot. Oliver takes Hal on a tour of the blighted structure and shames him for fighting on the side of the “fat cat,” not the impoverished kids who were roughing him up. GL gets defensive: “You’ve no cause to yell at me! I have a job … I do it!” GA counters by going full Godwin’s law: “Seems I’ve heard that line before … at the Nazi war trials!” That’s when the old black man appears and makes his j’accuse. Appropriately shamed, Hal agrees to help Oliver in taking down the landlord, which they eventually do after some crime-fighting mishegoss.

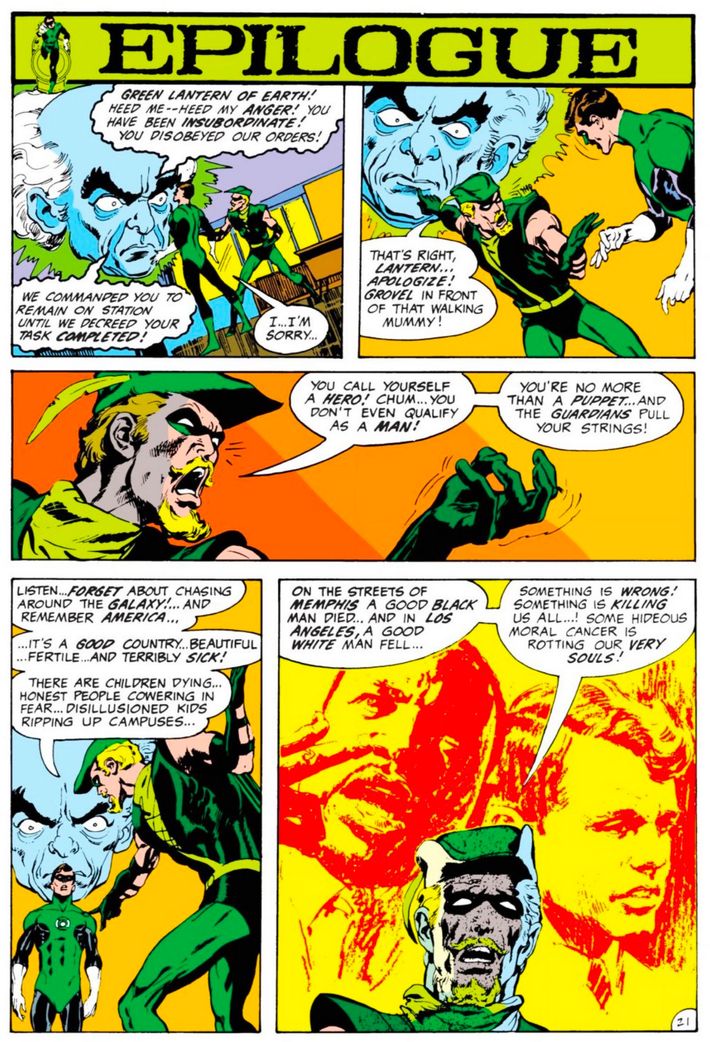

In an epilogue, Lantern’s alien bosses, the Guardians, excoriate him for wasting his time on his mission of social justice. Arrow, on the other hand, argues that their job has only just begun; that, in America, “Something is wrong! Something is killing us all! Some hideous moral cancer is rotting our very souls!” The Guardians concede that he has a point and send one of their number to Earth in human guise to accompany Oliver and Hal on, of all things, a road trip. “There’s a fine country out there someplace! Let’s go find it!” Oliver declares, hopping in a pickup truck. The concluding narration portends a new kind of story going forward: “Three set out together, moving through cities and villages and the majesty of the wilderness … searching for a special kind of truth … searching for themselves …”

The issue was a turning point for the series, and comics as a whole. For the next dozen-odd installments of Green Lantern, Hal, Oliver, and the Guardian encountered an array of social ills: environmental destruction, overpopulation, anti–Native American racism, the evils of the Nixon administration, and Manson-esque hippie cults, just to name a handful. The stories were a public sensation, garnering a write-up in the New York Times (“Shazam! Here Comes Captain Relevant,” read the headline), an analysis in a New York Magazine cover story (“The Radicalization of the Superheroes” was the title), and even a letter from New York City mayor John Lindsay in a much-publicized issue about Green Arrow’s sidekick getting addicted to heroin.

And then, as casually as the whole thing had come together, it dissipated. O’Neil and Adams — who, even at the height of the media circus, still hardly saw each other and rarely discussed stories — moved on to other projects and the Green Lantern / Green Arrow era was over. But its impact resonated in the years and decades that followed. A precedent had been set for superhero comics to address that “hideous moral cancer” that Oliver had talked about, and publishers and creators made repeated attempts to recapture that social relevance. Sometimes, the results were thrilling (Black Panther’s 1976 battle with the KKK, written by Don McGregor and penciled by Billy Graham, for example); other efforts are best left on the dustheap of history (a rape story line in Ms. Marvel leaps to mind, then leaps right out again).

The legacy of the run that began with Green Lantern No. 76 can be felt today in a bevy of progressive-minded superhero tales, from the nuanced religious tolerance of the rebooted Ms. Marvel to the pointed diversity of Lion Forge’s Catalyst Prime lineup. The “black skins” accusation regularly pops up in retrospectives of comics history, and the story in which it was contained has been reprinted over and over again in DC collected editions. Future generations won’t lack for opportunities to find out what all the fuss is about. O’Neil seems almost a little uncomfortable at all the attention paid to stuff he did primarily to earn a paycheck. “I hear about how that was a landmark series and so on,” he tells me, “but I’m looking at a Green Lantern / Green Arrow $75 hardcover edition across the room as we speak, and I certainly never anticipated anything like that.”

On the other side of the coin, Adams relishes the way he and his arm’s-length partner made history. “It made a difference and it woke up generations to the idea that comic books aren’t just for kids,” he says — but emphasizes that he hopes kid readers got the message. “As far as I know, no kid ever bought a children’s book himself with his own money, but they’ll buy comic books. So we better make them good … don’t you think?”