My only complaint about Thi Bui’s debut graphic memoir, which tells the sweeping tale of her family’s lives in Vietnam and the United States, relates to its title. The Best We Could Do is a fine moniker, but the name of this breathtaking work’s sixth chapter would fit the entire book even better: “The Chessboard.” Bui’s story is constructed like one, with the various members of her immediate and extended family beginning in the same place but moving away from it erratically, in fits and starts, eternally out of sync, and occasionally blocking each other’s paths. Nevertheless, they all push toward the same goal. In this case, that goal is understanding, be it on an individual or collective level. How did we end up here, the story seems to ask, on the other side, so hopelessly jumbled?

As with chess (as well as its Vietnamese counterpart, cờ tướng, which notably appears in the book), this family’s journey is maddeningly slow and constrained by a byzantine set of rules. They’re refugees escaping to America from a region America burned to the ground, and Uncle Sam doesn’t tend to make such a process easy. When Bui began work on The Best We Could Do in 2005, she couldn’t have predicted the significance it would hold when it was released in 2017, but now that it’s here, it feels like one of the first great works of socially relevant comics art of the Trump era.

By casting light on our present refugee crisis through the tilted mirror of the post-Vietnam one, Bui situates her tome alongside the winner of last year’s Pulitzer Prize for fiction, Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Sympathizer. Both narratives are vital for the way they grant oft-generalized populations not just faces and names, but also political leanings, class backgrounds, personal failings, and all the other things that make a human. Nguyen provides a glowing cover blurb for Bui, declaring The Best We Could Do to be “a book to break your heart and heal it.”

His endorsement is well-deserved, but that phrase feels too sentimental for what the reader finds inside. Though Bui’s story is much less relentless in its cynicism than The Sympathizer, it’s still as hardheaded as it is heartfelt. The vague outline of the Bui clan’s saga is familiar for any immigrant story: Family starts in one place, has a hard journey to get to another, struggles to settle, and eventually finds some kind of emotional synthesis. However, Bui presents that saga in a way that is narratively intricate, intellectually fastidious, and visually stunning.

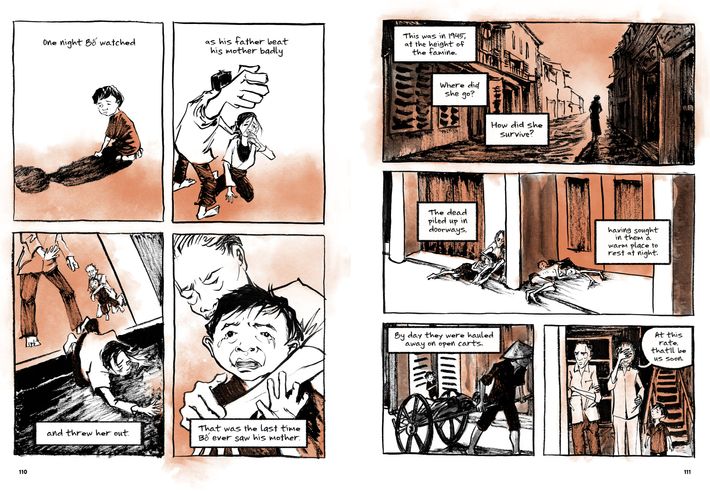

In fact, the second-best title for the book might be the name of the first chapter: “Labor.” In the best possible way, one feels how soaked The Best We Could Do is with sweat and tears. It begins with the birth of the author’s child and ends with her musings on where he’ll go in life, and everything that transpires in between is deliberately fragmentary, nonlinear, and stutter-stepped — paralleling the history of a family perpetually beset by tragedies large and small. The book will no doubt draw comparisons to comics’ most famed immigrant story, Art Spiegelman’s Maus, but where that story marched in mostly straight lines, Bui’s writhes and convulses.

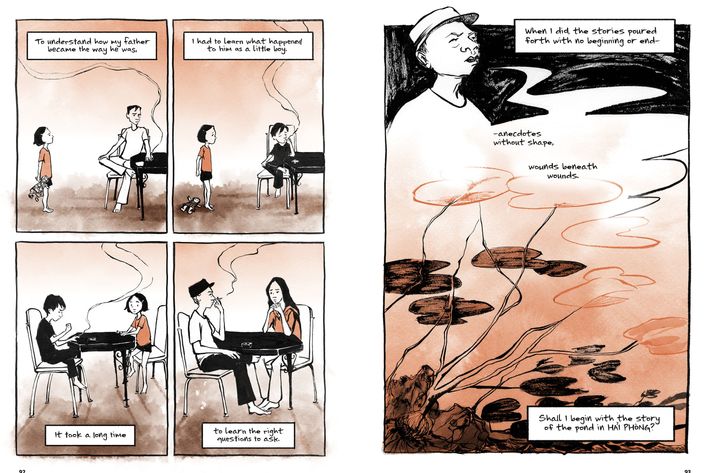

That story is only occasionally focused on Bui herself. The other time is spent with her attempting to grasp the individual realities of her family members, especially her mother — she wants to “let her be not what I want her to be, but someone independent, self-determining, and free” (a set of adjectives that echo the macro-level aspirations of Bui’s birthplace in the past century). In doing so, she uncovers significant events stretching from the turn of the last century through Vietnam’s bloody attempts at liberation from France, Japan, and the United States. They are presented more or less in the order she came across them, not the order of how they originally happened — a clever choice, reminding us that all historical memory is as situated in our individual personal chronology as it is in any objective one.

The tale she tells in that stutter-stepped way benefits from Bui’s astounding eye for detail. She’ll craft a map to convey how the remoteness of the city of Nha Trang allowed her mother to grow up in luxurious privilege, but we feel the lived experience of that privilege when she notes her mother’s childhood anger at the “unfairness” of storybooks always depicting “girls from rich families who were mean and less talented.” We hear of General Nguyễn Ngọc Loan, the gun-wielder in the infamous “Saigon execution” photograph, but not as a historical cliché; rather, we see the time he declined to kill Bui’s father and merely told an underling, “Give this hippie a haircut.” Those kinds of moments — rendered with evocatively elegant ink-work and rust-red watercolors — have more insight and empathy about the people of Vietnam than all of Apocalypse Now and Platoon.

The artwork possesses a deceptive simplicity that is particular to the comics medium. It’s an artistic tradition that rewards directness of both word and image, and Bui — despite being a schoolteacher with no published comic books prior to this one — dances within that tradition better than most. Her humans have sparse faces: often just eyebrows, dot eyes, two lines for a nose, and a few mouth strokes. That minimalism packs an emotional wallop, since Bui has given the reader a prime example of what theorist Scott McCloud calls “masking”: faces so basic that they cut past our defenses and make us empathize more than we would with more detail. She draws on a range of visual traditions, too, from the figure drawing of Alison Bechdel to the landscapes of Vietnamese silk scrolls.

Yet the most devastating simplicity comes in the form of Bui’s prose. I set out to dog-ear every brilliant piece of compact phrasing; my book is now twice as thick on the top as it is on the bottom. For example, the page on which she uses three sentences to describe the way parenthood’s tension begins just after the first cry of a newborn: “The struggle to bring a life into this world is rewarded by that cry. It is a single-minded effort, uncluttered and clear in its objective. What follows afterward — that is, the rest of the child’s life — is another story.”

Such a story is the one Bui sets out to tell for not just herself but everyone with whom she shares blood. Her struggle is Sisyphean, as the journey after the birth of a person or a country is hopelessly tangled and contradictory. The only thing that is certain is momentum: As long as there is life, those living will move; even when they die, their specters will move in endless leaps across the neurons of those who remember them. As Bui narrates near the end, “This — not any particular piece of Vietnamese culture — is my inheritance, the inexplicable need and extraordinary ability to run when the shit hits the fan. My refugee reflex.” Lucky for us, this refugee stopped running just long enough to tell us of her marathon.